The historic vote this week by a slim majority of the British people to leave the European Union –the so-called “Brexit” – signals a major political and economic challenge. But the Brexit also has a significant moral significance that goes beyond the UK. How we as nations understand borders, sovereignty, and other peoples speaks volumes to our deeper commitments to peace, solidarity, human rights, and the common good. Indeed, the decision to leave the European Union and the accompanying campaign vitriol against “others” signals a threat to one of the most important legacies of 20th Century Social Catholicism.

The Catholic Roots of the EU

While often under appreciated, Catholic social movements played a key role in the development of the European Union and the idea of a united Europe. The first proposals for a confederation of modern states came from French monks Emeric Crucé (1590–1648) and Charles-Irenée Castel de Saint-Pierre (1658-1743) who were inspired by the “catholic” idea and saw a union as the only way to bring about peace in a divided continent.

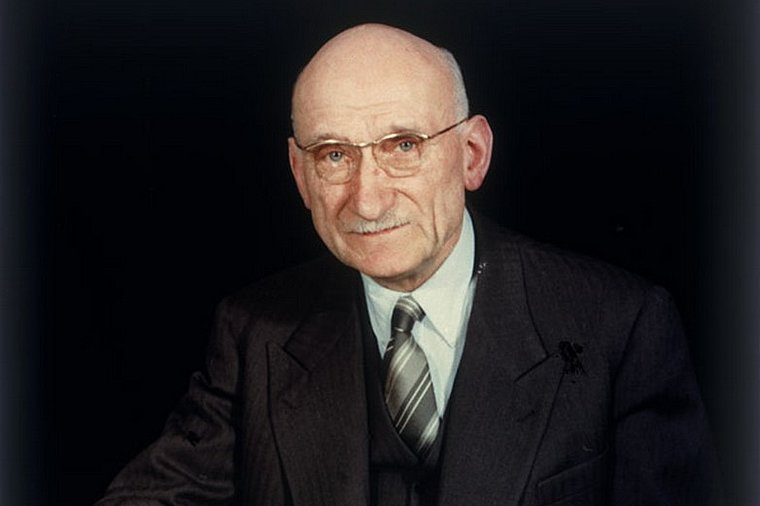

20th Century Catholic intellectuals and political figures, many formed by Catholic social movements, were among the key architects of the European infrastructure. Among “founding fathers” of the EU, nearly half were actively formed in movements of social Catholicism. Robert Schuman, for example, drew heavily on the Catholic intellectual tradition in his vision for a united Europe. Alcide De Gasperi, Konrad Adenauer, Pierre Werner were involved in the International Movement of Catholic Students (IMCS-Pax Romana) in leadership positions while they were university students. And Jacques Delors was deeply shaped by his engagement in the Young Christian Students and Young Christian Worker movements.

At the core of the European idea are values shared and promoted by Catholic social teaching: human dignity, freedom of movement, workers’ rights, culture, peace, social development and ecological concern. Moreover, the project embodies in a very real way Catholic teaching on the limits of borders and the need to transcend nationalism and false notions of sovereignty. This can be seen in the way that the values of solidarity and subsidiarity were explicitly mentioned in the EU’s Draft Constitution.

Pope Francis’ Call for a Stronger European Union

While imperfect, like any human institution, the European Union has been a remarkable sign of social, political, and cultural unity after centuries of division and war. This effort has won the praise of popes for the past fifty years. Pope Francis, for example, praised the the social and ecological commitments of the EU in his address to the members of the European Parliament last November and challenged them to deepen their commitments to human dignity, and in particular, the rights of migrants and religious minorities.

More recently, Francis developed his challenge to Europe upon receiving the Charlemagne Prize. For Francis, the problem of the European Union is not, as the Brexit populists claim, that it goes too far, but that it doesn’t go far enough. “What has happened,” the pope asks, “to you, the Europe of humanism, the champion of human rights, democracy and freedom?.” These are values that need to be developed and deepened he argued in relation to three points:

Integration and Multiculturalism

First, he calls Europe to redevelop its capacity to integrate difference, including the reality of migrants:

“The identity of Europe is, and always has been, a dynamic and multicultural identity… Time is teaching us that it is not enough simply to settle individuals geographically: the challenge is that of a profound cultural integration…The community of European peoples will thus be able to overcome the temptation of falling back on unilateral paradigms and opting for forms of “ideological colonization”. Instead, it will rediscover the breadth of the European soul, born of the encounter of civilizations and peoples.

Dialogue

Second, Francis challenges the European Union to deepen its commitments to dialogue:

We are called to promote a culture of dialogue by every possible means and thus to rebuild the fabric of society. The culture of dialogue entails a true apprenticeship and a discipline that enables us to view others as valid dialogue partners, to respect the foreigner, the immigrant and people from different cultures as worthy of being listened to

Empowering Agents for the Future

Third, Francis calls on the European leaders to empower people, particularly young people to work for social change:

Everyone, from the smallest to the greatest, has an active role to play in the creation of an integrated and reconciled society. This culture of dialogue can come about only if all of us take part in planning and building it. The present situation does not permit anyone to stand by and watch other people’s struggles. On the contrary, it is a forceful summons to personal and social responsibility.

A Clash of Visions: Xenophobia or Inclusion

Clearly, the vision of Francis for an inclusive Europe committed to dialogue, encounter and inclusion stands in sharp contrast to the populist movements that are seeing a resurgence in Europe and the Americas. While Francis calls for welcoming strangers, going out to those at the margins, and dialogue, a wide range of political leaders including the UK Independence Party’s Nigel Farage, the Front national’s Marine Le Pen (France) and America’s own Donald Trump are demonizing other groups, especially Muslims and immigrants, calling to withdraw from international arrangements, and promising to build walls instead of bridges. Trump, in fact, has praised the recent vote as a “great” thing for the British to take their country back.

Clearly, the xenophobic and triumphalistic discourse fueling right-wing populist movements clash with the values of multiculturalism, dialogue, and participation advocated by Pope Francis (and shared by many who voted to stay in the EU). Indeed, in a very profound way, the xenophobic, racist and nationalistic discourse fueling right-wing populist movements in Europe and the US is antithetical to the values at the core of the European Movement and Catholic social teaching. There is no room for a culture of encounter in a culture of isolationism. Given this new reality, the church, as Francis himself urged, must “play her part” in witnessing to the unity of the human race and God’s merciful love:

God desires to dwell in our midst, but he can only do so through men and women who… have been touched by him and live for the Gospel, seeking nothing else. Only a Church rich in witnesses will be able to bring back the pure water of the Gospel to the roots of Europe. In this enterprise, the path of Christians towards full unity is a great sign of the times and a response to the Lord’s prayer “that they may all be one” (Jn 17:21).

This is not an easy task. Catholics and all people of good will need to join together and confront the culture of prideful isolationism with a Gospel culture of encounter and dialogue.

Leave A Comment

You must be logged in to post a comment.